From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (04-06)

IV. Things Never Seen Before and Thoughts Never Thought:

THE DISCOVERY OF NEW STARS IN THE WORLD SPACE AND THE MATERIALIZATION OF SPACE

Galileo & Descartes

I have already mentioned the Sidereus Nuncius1 of Galileo Galilei, a work of which the influence—and the importance—cannot be overestimated, a work which announced a series of discoveries more strange and more significant than any that had ever been made before. Reading it today we can no longer, of course, experience the impact of the unheard-of message; yet we can still feel the excitement and pride glowing beneath the cool and sober wording of Galileo's report:2

It is assuredly important to add to the great number of fixed stars that up to now men have been able to see by their natural sight, and to set before the eyes innumerable others which have never been seen before and which surpass the old and previously known [stars] in number more than ten times.

It is most beautiful and most pleasant to the sight to see the body of the moon, distant from us by nearly sixty semidiameters of the earth, as near as if it were at a distance of only two and a half of these measures.

[paragraph continues] So that

Then to have settled disputes about the Galaxy or Milky Way and to have made its essence manifest to the senses, and even more to the intellect, seems by no means a matter to be considered of small importance; in addition to this, to demonstrate directly the substance of those stars which all astronomers up to this time have called nebulous, and to demonstrate that it is very different from what has hitherto been believed, will be very pleasant and very beautiful.

But what by far surpasses all admiration, and what in the first place moved me to present it to the attention of astronomers and philosophers, is this: namely, that we have discovered four planets, neither known nor observed by any one before us, which have their periods around a certain big star of the number of the previously known ones, like Venus and Mercury around the sun, which sometimes precede

To sum up: mountains on the moon, new "planets" in the sky, new fixed stars in tremendous numbers, things that no human eye had ever seen, and no human mind conceived before. And not only this: besides these new, amazing and wholly unexpected and unforeseen facts, there was also the description of an astonishing invention, that of an instrument—the first scientific instrument—the perspicillum, which made all these discoveries possible and enabled Galileo to transcend the limitation imposed by nature—or by God—on human senses and human knowledge.3

No wonder that the Message of the Stars was, at first, received with misgivings and incredulity, and that it played a decisive part in the whole subsequent development of astronomical science, which from now on became so closely linked together with that of its instruments that every progress of the one implied and involved a progress of the other. One could even say that not only astronomy, but science as such, began, with Galileo's invention, a new phase of its development, the phase that we might call the instrumental one.

The perspicilli not only increased the number of the fixed, and errant, stars: they changed their aspect. I have already dealt with this effect of the use of the telescope. Yet it is worth while quoting Galileo himself on this subject:

According to Galileo, this "adventitious" and "accidental" character of the halo surrounding the stars is clearly demonstrated by the fact that, when they are seen at dawn, stars, even of the first magnitude, appear quite small; and even Venus, if seen by daylight, is hardly larger than a star of the last magnitude. Daylight, so to say, cuts off their luminous fringes; and not only light, but diaphanous clouds or black veils and colored glass have the same effect.5

This, indeed, is extremely important as it destroys the basis of Tycho Brahe's most impressive—for his contemporaries—objection to heliocentric astronomy, according to which the fixed stars—if the Copernican world-system were true—should be as big, nay much bigger, than the whole orbis magnus of the annual circuit of the earth. The perspicillum reduces their visible diameter from 2 minutes to 5 seconds and thus disposes of the necessity to increase the size of the fixed stars beyond that of the sun. Yet the decrease in size is more than compensated by an increase in number:6

Click to enlarge

FIGURE 4

Galileo's star-picture of the shield and sword of Orion

(from the Sidereus Nuncius, 1610)

As a second example we have depicted the six stars of Taurus, called the Pleiades (we say six, because the seventh is scarcely ever visible), which are enclosed in the sky within very narrow boundaries, and near which are adjacent more than forty other visible ones, none of which is more than half a degree distant from the aforesaid six.

We have already seen that the invisibility for the human eye of the fixed stars discovered by Galileo, and, accordingly, the role of his perspicillum in revealing them, could be interpreted in two different ways: it could be explained by their being (a) too small to be seen, (b) too far away. The perspicillum would act in the first case as a kind of celestial microscope, in enlarging, so to say, the stars to perceivable dimensions; in the second it would be a " telescope " and, so to say, bring the stars nearer to us, to a distance at which they become visible. The second interpretation, that which makes visibility a function of the distance, appears to us now to be the only one possible. Yet this was not the case in the seventeenth century. As a matter of fact both interpretations fit the optical data equally well and a man of that period had no scientific, but only philosophical, reasons for choosing between them. And it was for philosophical reasons that the prevailing trend of seventeenth century thinking rejected the first interpretation and adopted the second.

There is no doubt whatever that Galileo adopted it too, though he very seldom asserts it. As a matter of fact he does it only once, in a curious passage of his Letter to Ingoli where he tells the latter that:7

[paragraph continues] Indeed, in the debate about the finiteness or the infinity of the universe, the great Florentine, to whom modern science owes perhaps more than to any other man, takes no part. He never tells us whether he believes the one or the other. He seems not to have made up his mind, or even, though inclining towards infinity, to consider the question as being insoluble. He does not hide, of course, that in contradistinction to Ptolemy, Copernicus and Kepler, he does not admit the limitation of the world or its enclosure by a real sphere of fixed stars. Thus in the letter to Ingoli already quoted he tells him:9

[paragraph continues] And, what is more, not only is it not proved that they are arranged in a sphere but neither Ingoli himself,10

Consequently, once more in opposition to Ptolemy, Copernicus and Kepler, and in accordance with Nicholas of Cusa and Giordano Bruno, Galileo rejects the conception of a center of the universe where the earth, or the sun, should be placed, "the center of the universe which we do not know where to find or whether it exists at all." He even tells us that "the fixed stars are so many suns." Yet, in the selfsame Dialogue on the Two Greatest World-Systems from which the last two quotations are taken, discussing ex professo the distribution of the fixed stars in the universe, he does not assert that the stars are scattered in space without end:11

Simp.—I would rather take a middle way and would assign them a circle described about a determinate center and comprised within two spherical surfaces, to wit, one very high and concave, the other lower and convex betwixt which I would constitute the innumerable multitude of stars, but yet at diverse altitudes, and this might be called

Salv.—But now we have all this while, Simplicius, disposed the mundane bodies exactly according to the order of Copernicus. . . .

We can assuredly explain the moderation of Salviati, who does not criticize the conception presented by Simplicio—though he does not share it—and who accepts it, for the purpose of the discussion, as agreeing perfectly with Copernican astronomy, by the very nature of the Dialogue: a book intended for the "general reader," a book which aims at the destruction of the Aristotelian world-view in favor of that of Copernicus, a book which pretends, moreover, not to do it, and where, therefore, subjects both difficult and dangerous are obviously to be avoided.

We could even go as far as to discard the outright negation of the infinity of space in the Dialogue—which had to pass the censorship of the Church—and to oppose to it the passage of the letter to Ingoli where its possibility is just as strongly asserted. In the Dialogue, indeed, Galileo tells us, just as Kepler does, that it is:12

Whereas in the Letter to Ingoli he writes:13

[paragraph continues] We must not forget, however, that in the selfsame Dialogue where he so energetically denied the infinity of space, he makes Salviati tell Simplicio—just as he himself had told Ingoli—that:14

[paragraph continues] Moreover, we cannot reject the testimony of Galileo's Letter to Liceti, where, coming back to the problem of the finiteness and the infinity of the world, he writes:15

It is possible, of course, that all the pronouncements of Galileo have to be taken cum grano salis, and that the fate of Bruno, the condemnation of Copernicus in 1616,

his own condemnation in 1633 incited him to practise the virtue of prudence: he never mentions Bruno, either in his writings or in his letters; yet it is also possible—it is even quite probable—that this problem, like, generally speaking, the problems of cosmology or even of celestial mechanics, did not interest him very much. Indeed he concentrates on the question: a quo moventur projecta? but never asks: a quo moventur planetae? It may be, therefore, that, like Copernicus himself, he never took up the question, and thus never made the decision—though it is implied in the geometrization of space of which he was one of the foremost promoters—to make his world infinite. Some features of his dynamics, the fact that he never could completely free himself from the obsession of circularity—his planets move circularly around the sun without developing any centrifugal force in their motion—seem to suggest that his world was not infinite. If it was not finite it was probably, like the world of Nicholas of Cusa, indeterminate; and it is, perhaps, more than a pure contingent coincidence that in his letter to Liceti he uses the expression also employed by Cusa: interminate.

Be this as it may, it is not Galileo, in any case, nor Bruno, but Descartes who clearly and distinctly formulated principles of the new science, its dream de reductione scientiae ad mathematicam, and of the new, mathematical, cosmology. Though, as we shall see, he overshot the mark and by his premature identification of matter and space deprived himself of the means of giving a correct solution to the problems that seventeenth century science had placed before him.

The God of a philosopher and his world are correlated. Now Descartes’ God, in contradistinction to most previous Gods, is not symbolized by the things He created; He does not express Himself in them. There is no analogy between God and the world; no imagines and vestigia Dei in mundo; the only exception is our soul, that is, a pure mind, a being, a substance of which all essence consists in thought, a mind endowed with an intelligence able to grasp the idea of God, that is, of the infinite (which is even innate to it), and with will, that is, with infinite freedom. The Cartesian God gives us some clear and distinct ideas that enable us to find out the truth, provided we stick to them and take care not to fall into error. The Cartesian God is a truthful God; thus the knowledge about the world created by Him that our clear and distinct ideas enable us to reach is a true and authentic knowledge. As for this world, He created it by pure will, and even if He had some reasons for doing it, these reasons are only known to Himself; we have not, and cannot have, the slightest idea of them. It is therefore not only hopeless, but even preposterous to try to find out His aims. Teleological conceptions and explanations have no place and no value in physical science, just as they have no place and no meaning in mathematics, all the more so as the world created by the Cartesian God, that is, the world of Descartes, is by no means the colorful, multiform and qualitatively determined world of the Aristotelian, the world of our daily life and experience—that world is only a subjective world of unstable and inconsistent opinion based upon the untruthful testimony of confused and erroneous sense-perception—but a strictly uniform mathematical world, a world of geometry made

real about which our clear and distinct ideas give us a certain and evident knowledge. There is nothing else in this world but matter and motion; or, matter being identical with space or extension, there is nothing else but extension and motion.

The famous Cartesian identification of extension and matter (that is, the assertion that "it is not heaviness, or hardness, or color which constitutes the nature of body but only extension,"16 in other words, that "nature of body, taken generally, does not consist in the fact that it is a hard, or a heavy, or a colored thing, or a thing that touches our senses in any other manner, but only in that it is a substance extended in length, breadth and depth," and that conversely, extension in length, breadth and depth can only be conceived—and therefore can only exist—as belonging to a material substance) implies very far-reaching consequences, the first being the negation of the void, which is rejected by Descartes in a manner even more radical than by Aristotle himself.

Indeed, the void, according to Descartes, is not only physically impossible, it is essentially impossible. Void space—if there were anything of that kind—would be a contradictio in adjecto, an existing nothing. Those who assert its existence, Democritus, Lucretius and their followers, are victims of false imagination and confused thinking. They do not realize that nothing can have no properties and therefore no dimensions. To speak of ten feet of void space separating two bodies is meaningless; if there were a void, there would be no separation, and bodies separated by nothing would be in contact. And if there is separation and distance, this distance is not a length, breadth or depth of nothing but of something, that is, of

substance or matter, a "subtle" matter, a matter that we do not sense—that is precisely why people who are accustomed to imagining instead of thinking speak of void space—but nevertheless a matter just as real and as "material" (there are no degrees in materiality) as the "gross" matter of which trees and stones are made.

Thus Descartes does not content himself with stating, as did Giordano Bruno and Kepler, that there is no really void space in the world and that the world-space is everywhere filled with "ether." He goes much farther and denies that there is such a thing at all as "space," an entity distinct from "matter" that "fills" it. Matter and space are identical and can be distinguished only by abstraction. Bodies are not in space, but only among other bodies; the space that they "occupy" is not anything different from themselves:17

[paragraph continues] But that, of course, is an error. And,18

[paragraph continues] We can, indeed, divest and deprive any given body of all its sensible qualities and19

[paragraph continues] Thus,20

Consequently,21

The second important consequence of the identification of extension and matter consists in the rejection not only of the finiteness and limitation of space, but also that of the real material world. To assign boundaries to it becomes not only false, or even absurd, but contradictory. We cannot posit a limit without transcending it in this very act. We have to acknowledge therefore that the real world is infinite, or rather—Descartes, indeed, refuses to use this term in connection with the world—indefinite.

It is clear, of course, that we cannot limit Euclidean space. Thus Descartes is perfectly right in pursuing:22

There is no longer any need to discuss the question whether fixed stars are big or small, far or near; more exactly this problem becomes a factual one, a problem of astronomy and observational technics and calculation. The question no longer has metaphysical meaning since it is perfectly certain that, be the stars far or near, they are, like ourselves and our sun, in the midst of other stars without end.

It is exactly the same concerning the problem of the constitution of the stars. This, too, becomes a purely scientific, factual question. The old opposition of the earthly world of change and decay to the changeless world of the skies which, as we have seen, was not abolished by the Copernican revolution, but persisted as the opposition of the moving world of the sun and the planets to the motionless, fixed stars, disappears without trace. The unification and the uniformization of the universe in its contents and laws becomes a self-evident fact23—"The matter of the sky and of the earth is one and the same; and there cannot be a plurality of worlds"—at least if we take the term "world" in its full sense, in which it was used by Greek and mediaeval tradition, as meaning a complete and self-centered whole. The world is not an unconnected multiplicity of such wholes utterly separated from each other: it is a unity in which—just as in the universe of Giordano Bruno (it is a pity that Descartes does not use Bruno's terminology)—there are an infinite number of subordinate and interconnected systems, such as our system with its sun and planets, immense vortices of matter everywhere identical joining and limiting each other in boundless space.24

The infinity of the world seems thus to be established beyond doubt and beyond dispute. Yet, as a matter of fact, Descartes never asserts it. Like Nicholas of Cusa two centuries before him, he applies the term "infinite" to God alone. God is infinite. The world is only indefinite.

The idea of the infinite plays an important part in the philosophy of Descartes, so important that Cartesian-ism may be considered as being wholly based upon that idea. Indeed, it is only as an absolutely infinite being that God can be conceived; it is only as such that He can be proved to exist; it is only by the possession of this idea that man's very nature—that of a finite being endowed with the idea of God—can be defined.

Moreover, it is a very peculiar, and even unique, idea: it is certainly a clear and positive one—we do not reach infinity by negating finitude; on the contrary, it is by negating the infinite that we conceive finiteness, and yet it is not distinct. It so far surpasses the level of our finite understanding that we can neither comprehend nor even analyse it completely. Descartes thus rejects as perfectly worthless all the discussions about the infinite, especially those de compositione continui, so popular in the late Middle Ages, and also in the xviith century. He tells us that:25

In this way we shall avoid the Keplerian objections based upon the absurdity of an actually infinite distance between ourselves and a given star, and also the theological objections against the possibility of an actually infinite creature. We shall restrict ourselves to the assertion that, just as in the series of numbers, so in world-extension we can always go on without ever coming to an end:28

The Cartesian distinction between the infinite and the indefinite thus seems to correspond to the traditional one between actual and potential infinity, and Descartes’ world, therefore, seems to be only potentially infinite. And yet . . . what is the exact meaning of the assertion that the limits of the world cannot be found by us? Why can they not? Is it not, in spite of the fact that we do not understand it in a positive way, simply because there are none? Descartes, it is true, tells us that God alone is clearly understood by us to be infinite and infinitely, that is absolutely, perfect. As for other things:27

But it is hard to admit that the impossibility of conceiving a limit to space must be explained as a result of a defect of our understanding, and not as that of an insight into the nature of the extended substance itself. It is even harder to believe that Descartes himself could seriously espouse this opinion, that is, that he could really think that his inability to conceive, or even imagine, a finite world could be explained in this way. This is all the more so as somewhat farther on, in the beginning of the third part of the Principia Philosophiae, from which

the passages we have quoted are taken, we find Descartes telling us that in order to avoid error,28

The second of these necessary precautions is that,29

which seems to teach us that the limitations of our reason manifest themselves in assigning limits to the world, and not in denying outright their existence. Thus, in spite of the fact that Descartes, as we shall see in a moment, had really very good reasons for opposing the "infinity" of God to the "indefiniteness" of the world, the common opinion of his time held that it was a pseudo-distinction, made for the purpose of placating the theologians.

That is, more or less, what Henry More, the famous Cambridge Platonist and friend of Newton, was to tell him.

V. Indefinite Extension or Infinite Space

Descartes & Henry More

Henry More was one of the first partisans of Descartes in England even though, as a matter of fact, he never was a Cartesian and later in life turned against Descartes and even accused the Cartesians of being promoters of atheism.1 More exchanged with the French philosopher a series of extremely interesting letters which throws a vivid light on the respective positions of the two thinkers.2

More starts, naturally, by expressing his admiration for the great man who has done so much to establish truth and dissipate error, continues by complaining about the difficulty he has in understanding some of his teachings, and ends by presenting some doubts, and even some objections.

Thus, it seems to him difficult to understand or to admit the radical opposition established by Descartes between body and soul. How indeed can a purely spiritual soul, that is, something which, according to Descartes, has no extension whatever, be joined to a purely material

body, that is, to something which is only and solely extension? Is it not better to assume that the soul, though immaterial, is also extended; that everything, even God, is extended? How could He otherwise be present in the world?

Thus More writes:3

Having thus established that the concept of extension cannot be used for the definition of matter since it is too wide and embraces both body and spirit which both are extended, though in a different manner (the Cartesian demonstration of the contrary appears to More to be not only false but even pure sophistry), More suggests secondly that matter, being necessarily sensible, should be defined only by its relation to sense, that is, by tangibility.

[paragraph continues] But if Descartes insists on avoiding all reference to sense-perception, then matter should be defined by the ability of bodies to be in mutual contact, and by the impenetrability which matter possesses in contradistinction to spirit. The latter, though extended, is freely penetrable and cannot be touched. Thus spirit and body can co-exist in the same place, and, of course, two—or any number of—spirits can have the same identical location and "penetrate" each other, whereas for bodies this is impossible.

The rejection of the Cartesian identification of extension and matter leads naturally to the rejection by Henry More of Descartes’ denial of the possibility of vacuum. Why should not God be able to destroy all matter contained in a certain vessel without—as Descartes asserts—its walls being obliged to come together? Descartes, indeed, explains that to be separated by "nothing" is contradictory and that to attribute dimensions to "void" space is exactly the same as to attribute properties to nothing; yet More is not convinced, all the more so as "learned Antiquity"—that is Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius—was of quite a different opinion. It is possible, of course, that the walls of the vessel will be brought together by the pressure of matter outside them. But if that happens, it will be because of a natural necessity and not because of a logical one. Moreover, this void space will not be absolutely void, for it will continue to be filled with God's extension. It will only be void of matter, or body, properly speaking.

In the third place Henry More does not understand the "singular subtlety" of Descartes’ negation of the existence of atoms, of his assertion of the indefinite divisibility

of matter, combined with the use of corpuscular conceptions in his own physics. To say that the admission of atoms is limiting God's omnipotence, and that we cannot deny that God could, if He wanted to, divide the atoms into parts, is of no avail: the indivisibility of atoms means their indivisibility by any created power, and that is something that is perfectly compatible with God's own power to divide them, if He wanted to do so. There are a great many things that He could have done, but did not, or even those that He can do but does not. Indeed, if God wanted to preserve his omnipotence in its absolute, status, He would never create matter at all: for, as matter is always divisible into parts that are themselves divisible, it is clear that God will never be able to bring this division to its end and that there will always be something which evades His omnipotence.

Henry More is obviously right and Descartes himself, though insisting on God's omnipotence and refusing to have it limited and bounded even by the rules of logic and mathematics, cannot avoid declaring that there are a great many things that God cannot do, either because to do them would be, or imply, an imperfection (thus, for instance, God cannot lie and deceive), or because it would make no sense. It is just because of that, Descartes asserts, that even God cannot make a void, or an atom. True, according to Descartes, God could have created quite a different world and could have made twice two equal to five, and not to four. On the other hand, it is equally true that He did not do it and that in this world even God cannot make twice two equal to anything but four.

From the general trend of his objections it is clear that the Platonist, or rather Neoplatonist, More was deeply

influenced by the tradition of Greek atomism, which is not surprising in view of the fact that one of his earliest works bears the revealing title, Democritus Platonissans. . .4

What he wants is just to avoid the Cartesian geometrization of being, and to maintain the old distinction between space and the things that are in space; that are moving in space and not only relatively to each other; that occupy space in virtue of a special and proper quality or force—impenetrability—by which they resist each other and exclude each other from their "places."

Grosso modo, these are Democritian conceptions and that explains the far-reaching similarity of Henry More's objections to Descartes to those of Gassendi, the chief representative of atomism in the XVIIth century.5 Yet Henry More is by no means a pure Democritian. He does not reduce being to matter. And his space is not the infinite void of Lucretius: it is full, and not full of "ether" like the infinite space of Bruno. It is full of God, and in a certain sense it is God Himself as we shall see more clearly hereafter.

Let us now come to More's fourth and most important objection to Descartes:6

[paragraph continues] Having thus impaled Descartes on the horns of the dilemma, More continues:8

by arguments that Descartes would be bound to accept.9

To the perplexity and objections of his English admirer and critic Descartes replies10—and his answer is surprisingly mild and courteous—that it is an error to define matter by its relation to senses, because by doing so we are in danger of missing its true essence, which does not depend on the existence of men and which would be the same if there were no men in the world; that, moreover, if divided into sufficiently small parts, all matter becomes utterly insensible; that his proof of the identity of extension and matter is by no means a sophism but is as clear and demonstrative as it could be; and that it is perfectly unnecessary to postulate a special property of impenetrability in order to define matter because it is a mere consequence of its extension.

Turning then to More's concept of immaterial or spiritual extension, Descartes writes:11

Nothing of that kind applies to God, or to our souls, which are not objects of imagination, but of pure understanding, and have no separable parts, especially no parts of determinate size and figure. Lack of extension is precisely the reason why God, the human soul, and any number of angels can be all together in the same place. As for atoms and void, it is certain that, our intelligence being finite and God's power infinite, it is not proper for us to impose limits upon it. Thus we must boldly assert "that God can do all that we conceive to be possible, but not that He cannot do what is repugnant to our concept." Nevertheless, we can judge only according to our concepts, and, as it is repugnant to our manner of thinking to conceive that, if all matter were removed from a vessel, extension, distance, etc., would still remain, or that parts of matter be indivisible, we say simply that all that implies contradiction.

Descartes’ attempt to save God's omnipotence and, nevertheless, to deny the possibility of void space as incompatible with our manner of thinking, is, to say the truth, by no means convincing. The Cartesian God is a Deus verax and He guarantees the truth of our clear and

distinct ideas. Thus it is not only repugnant to our thought, but impossible that something of which we clearly see that it implies contradiction be real. There are no contradictory objects in this world, though there could have been in another.

Coming now to More's criticism of his distinction between " infinite " and " indefinite," Descartes assures him that it is not because of12

Thus I am surprised that you not only seem to want to do so, as when you say that if extension is infinite only in respect to us then extension in truth will be finite, etc., but that you imagine beyond this one a certain divine extension, which would stretch farther than the extension of bodies, and thus suppose that God has partes extra partes, and that He is divisible, and, in short, attribute to Him all the essence of a corporeal being.

Descartes, indeed, is perfectly justified in pointing out that More has somewhat misunderstood him: a space

beyond the world of extension has never been admitted by him as possible or imaginable, and even if the world had these limits which we are unable to find, there certainly would be nothing beyond them, or, better to say, there would be no beyond. Thus, in order to dispel completely More's doubts, he declares:13

But I think, nevertheless, that there is a very great difference between the amplitude of this corporeal extension and the amplitude of the divine, I shall not say, extension, because properly speaking there is none, but substance or essence; and therefore I call this one simpliciter infinite, and the other, indefinite.

Descartes is certainly right in wanting to maintain the distinction between the "intensive" infinity of God, which not only excludes all limit, but also precludes all multiplicity, division and number, from the mere endlessness, indefiniteness, of space, or of the series of numbers, which necessarily include and presuppose them. This distinction, moreover, is quite traditional, and we have seen it asserted not only by Nicholas of Cusa, but even by Bruno.

Henry More does not deny this distinction; at least not completely. In his own conception it expresses itself in the opposition between the material and the divine extension. Yet, as he states it in his second letter to

[paragraph continues] Descartes,14 it has nothing to do with Descartes’ assertion that there may be limits to space and with his attempt to build a concept intermediate between the finite and the infinite; the world is finite or infinite, tertium non dater. And if we admit, as we must, that God is infinite and everywhere present, this "everywhere" can only mean infinite space. In this case, pursues More, re-editing an argument already used by Bruno, there must also be matter everywhere, that is, the world must be infinite.15

[paragraph continues] Nor is it absurd or inconsiderate to say that, if the extension is infinite only quoad nos, it will, in truth and in reality, be finite:16

As for Descartes’ contention that the impossibility of the void already results from the fact that "nothing" can have no properties or dimensions and therefore cannot be measured, More replies by denying this very premise:17

We have seen Henry More defend, against Descartes, the infinity of the world, and even tell the latter that his own physics necessarily implies this infinity. Yet it seems that, at times, he feels himself assailed by doubt. He is perfectly sure that space, that is, God's extension, is infinite. On the other hand, the material world may, perhaps, be finite. After all, nearly everybody believes it; spatial infinity and temporal eternity are strictly parallel, and so both seem to be absurd. Moreover Cartesian cosmology can be put in agreement with a finite world. Could

[paragraph continues] Descartes not tell what would happen, in this case, if somebody sitting at the extremity of the world pushed his sword through the limiting wall? On the one hand, indeed, this seems easy, as there would be nothing to resist it; on the other, impossible, as there would be no place where it could be pushed.18

Descartes’ answer to this second letter of More19 is much shorter, terser, less cordial than to the first one. One feels that Descartes is a bit disappointed in his correspondent who obviously does not understand his, Descartes’, great discovery, that of the essential opposition between mind and extension, and who persists in attributing extension to souls, angels, and even to God. He restates20

If there were no world, there would be no time either. To More's contention that the intermundium would last a certain time, Descartes replies:21

Indeed, it would mean introducing time into God, and thus making God a temporal, changing being. It would mean denying His eternity, replacing it by mere sempiternity—an error no less grave than the error of making Him an extended thing. For in both cases God is menaced with losing His transcendence, with becoming immanent to the world.

Now Descartes’ God is perhaps not the Christian God, but a philosophical one.22 He is, nevertheless, God, not the soul of the world that penetrates, vivifies and moves it. Therefore he maintains, in accordance with mediaeval tradition, that, in spite of the fact that in God power and essence are one—an identity pointed out by More in favour of God's actual extension—God has nothing in common with the material world. He is a pure mind, an infinite mind, whose very infinity is of a unique and incomparable non-quantitative and non-dimensional kind, of which spatial extension is neither an image nor even a symbol. The world therefore, must not be called infinite; though of course we must not enclose it in limits:23

Once more Descartes asserts that God's presence in the world does not imply His extension. As for the world

itself which More wants to be either simpliciter finite, or simpliciter infinite, Descartes still refuses to call it infinite. And yet, either because he is somewhat angry with More, or because he is in a hurry and therefore less careful, he practically abandons his former assertion about the possibility of the world's having limits (though we cannot find them) and treats this conception in the same manner in which he treated that of the void, that is, as nonsensical and even contradictory; thus, rejecting as meaningless the question about the possibility of pushing a sword through the boundary of the world, he says:24

Henry More, needless to say, was not convinced—one philosopher seldom convinces another. He persisted, therefore, in believing "with all the ancient Platonists" that all substance, souls, angels and God are extended, and that the world, in the most literal sense of this word, is in God just as God is in the world. More accordingly sent Descartes a third letter,25 which he answered,26 and a fourth,27 which he did not.28 I shall not attempt to examine them here as they bear chiefly on questions which, though interesting in themselves—for example, the discussion about motion and rest—are outside our subject.

Summing up, we can say that we have seen Descartes, under More's pressure, move somewhat from the position he had taken at first: to assert the indefiniteness of the world, or of space, does not mean, negatively, that perhaps it has limits that we are unable to ascertain; it means, quite positively, that it has none because it would be contradictory to posit them. But he cannot go farther. He has to maintain his distinction, as he has to maintain the identification of extension and matter, if he is to maintain his contention that the physical world is an object of pure intellection and, at the same time, of imagination—the precondition of Cartesian science—and that the world, in spite of its lack of limits, refers us to God as its creator and cause.

Infinity, indeed, has always been the essential character, or attribute, of God; especially since Duns Scotus, who could accept the famous Anselmian a priori proof of the existence of God (a proof revived by Descartes) only after he had "colored" it by substituting the concept of the infinite being (ens infinitum) for the Anselmian concept of a being than which we cannot think of a greater (ens quo maius cogitari nequit). Infinity thus—and it is particularly true of Descartes whose God exists in virtue of the infinite "superabundance of His essence" which enables Him to be His own cause (causa sui) and to give Himself His own existence29—means or implies being, even necessary being. Therefore it cannot be attributed to creature. The distinction, or opposition, between God and creature is parallel and exactly equivalent to that of infinite and of finite being.

VI. God and Space, Spirit and Matter

Henry More

The breaking off of the correspondence with—and the death of—Descartes did not put an end to Henry More's preoccupation with the teaching of the great French philosopher. We could even say that all his subsequent development was, to a very great extent, determined by his attitude towards Descartes: an attitude consisting in a partial acceptance of Cartesian mechanism joined to a rejection of the radical dualism between spirit and matter which, for Descartes, constituted its metaphysical background and basis.

Henry More enjoys a rather bad reputation among historians of philosophy, which is not surprising. In some sense he belongs much more to the history of the hermetic, or occultist, tradition than to that of philosophy proper; in some sense he is not of his time: he is a spiritual contemporary of Marsilio Ficino, lost in the disenchanted world of the "new philosophy" and fighting a losing battle against it. And yet, in spite of his partially anachronistic standpoint, in spite of his invincible trend towards syncretism which makes him jumble together

[paragraph continues] Plato and Aristotle, Democritus and the Cabala, the thrice great Hermes and the Stoa, it was Henry More who gave to the new science—and the new world view—some of the most important elements of the metaphysical framework which ensured its development: this because, in spite of his unbridled phantasy, which enabled him to describe at length God's paradise and the life and various occupations of the blessed souls and spirits in their post-terrestrial existence, in spite of his amazing credulity (equalled only by that of his pupil and friend, fellow of the Royal Society, Joseph Glanvill,1 the celebrated author of the Scepsis scientifica), which made him believe in magic, in witches, in apparitions, in ghosts, Henry More succeeded in grasping the fundamental principle of the new ontology, the infinitization of space, which he asserted with an unflinching and fearless energy.

It is possible, and even probable, that, at the time of his Letters to Descartes (1648), Henry More did not yet recognize where the development of his conceptions was ultimately to lead him, all the more so as these conceptions are by no means "clear" and "distinct." Ten years later, in his Antidote against Atheism2 and his Immortality of the Soul3 he was to give them a much more precise and definite shape; but it was only in his Enchiridium metaphysicum,4 ten years later still, that they were to acquire their final form.

As we have seen, Henry More's criticism of Descartes’ identification of space or extension with matter follows two main lines of attack. On the one hand it seems to him to restrict the ontological value and importance of extension by reducing it to the role of an essential attribute of matter alone and denying it to spirit, whereas it is an

attribute of being as such, the necessary precondition of any real existence. There are not, as Descartes asserts, two types of substance, the extended and the unextended. There is only one type: all substance, spiritual as well as material, is extended.

On the other hand, Descartes, according to More, fails to recognize the specific character both of matter and of space, and therefore misses their essential distinction as well as their fundamental relation. Matter is mobile in space and by its impenetrability occupies space; space is not mobile and is unaffected by the presence, or absence, of matter in it. Thus matter without space is unthinkable, whereas space without matter, Descartes notwithstanding, is not only an easy, but even a necessary idea of our mind.

Henry More's pneumatology does not interest us here; still, as the notion of spirit plays an important part in his—and not only his—interpretation of nature, and is used by him—and not only by him—to explain natural processes that cannot be accounted for or "demonstrated" on the basis of purely mechanical laws (such as magnetism, gravity and so on), we shall have to dwell for a moment on his concept of it.

Henry More was well aware that the notion of "spirit" was, as often as not, and even more often than not, presented as impossible to grasp, at least for the human mind,5

As we see, the method used by Henry More to arrive at the notion or definition of spirit is rather simple. We have to attribute to it properties opposite or contrary to those of body: penetrability, indivisibility, and the faculty to contract and dilate, that is, to extend itself without loss of continuity, into a smaller or larger space. This last property was for a very long time considered as belonging to matter also, but Henry More, under the conjoint influence of Democritus and Descartes, denies it to matter, or body, which is, as such, incompressible and always occupies the same amount of space.

In The Immortality of the Soul Henry More gives us an even clearer account both of his notion of spirit and

of the manner in which this notion can be determined. Moreover he attempts to introduce into his definition a sort of terminological precision. Thus, he says,6 "by Actual Divisibility I understand Discerpibility, gross tearing or cutting of one part from the other." It is quite clear that this "discerpibility" can only belong to a body and that you cannot tear away and remove a piece of a spirit.

As for the faculty of contraction and dilation, More refers it to the "essential spissitude" of the spirit, a kind of spiritual density, fourth mode, or fourth dimension of spiritual substance that it possesses in addition to the normal three of spatial extension with which bodies are alone endowed.7 Thus, when a spirit contracts, its "essential spissitude" increases; it decreases, of course, when it dilates. We cannot, indeed, imagine the "spissitude" but this "fourth Mode," Henry More tells us,8 "is as easy and familiar to my Understanding as that of the Three dimensions to my sense or Phansy."

The definition of spirit is now quite easy:9

Now I appeal to any man that can set aside prejudice, and has the free use of his Faculties, whether every term of the Definition of a Spirit be not as intelligible and congruous to Reason, as in that of a Body. For the precise Notion of Substance is the same in both, in which, I conceive, is comprised

I am rather doubtful whether the modern reader—even if he puts aside prejudice and makes free use of his faculties—will accept Henry More's assurance that it is as easy, or as difficult, to form the concept of spirit as that of matter, and whether, though recognizing the difficulty of the latter, he will not agree with some of More's contemporaries in "the confident opinion" that "the very notion of a Spirit were a piece of Nonsense and perfect Incongruity." The modern reader will be right, of course, in rejecting More's concept, patterned obviously upon that of a ghost. And yet he will be wrong in assuming it to be pure and sheer nonsense.

In the first place, we must not forget that for a man of the seventeenth century the idea of an extended, though not material, entity was by no means something strange or even uncommon. Quite the contrary: these

entities were represented in plenty in their daily life as well as in their scientific experience.

To begin with, there was light, assuredly immaterial and incorporeal but nevertheless not only extending through space but also, as Kepler does not fail to point out, able, in spite of its immateriality, to act upon matter, and also to be acted upon by the latter. Did not light offer a perfect example of penetrability, as well as of penetrating power? Light, indeed, does not hinder the motion of bodies through it, and it can also pass through bodies, at least some of them; furthermore, in the case of a transparent body traversed by light, it shows us clearly that matter and light can coexist in the same place.

The modern development of optics did not destroy but, on the contrary, seemed to confirm this conception: a real image produced by mirrors or lenses has certainly a determinate shape and location in space. Yet, is it body? Can we disrupt or "discerp" it, cut off and take away a piece of this image?

As a matter of fact, light exemplifies nearly all the properties of More's "spirit," those of "condensation" and "dilatation" included, and even that of "essential spissitude" that could be represented by the intensity of light's varying, just like the "spissitude," with its "contraction" and "dilatation."

And if light were not sufficiently representative of this kind of entity, there were magnetic forces that to William Gilbert seemed to belong to the realm of animated much more than to purely material being: "there was attraction (gravity) that freely passed through all bodies and could be neither arrested nor even affected by any.

Moreover, we must not forget that the "ether," which played such an important role in the physics of the nineteenth century (which maintained as firmly or even more firmly than the seventeenth the opposition between "light" and "matter," an opposition that is by no means completely overcome even now), displayed an ensemble of properties even more astonishing than the "spirit" of Henry More. And finally, that the fundamental entity of contemporary science, the "field," is something that possesses location and extension, penetrability and indiscerpibility. . . . So that, somewhat anachronistically, of course, one could assimilate More's " spirits," at least the lowest, unconscious degrees of them, to some kinds of fields.11a

But let us now come back to More. The greater precision achieved by him in the determination of the concept of spirit led necessarily to a stricter discrimination between its extension and the space in which, like everything else, it finds itself, concepts that were somehow merged together into the divine or spiritual extension opposed by More to the material Cartesian one. Space or pure immaterial extension will be distinguished now from the " spirit of nature " that pervades and fills it, that acts upon matter and produces the above-mentioned non-mechanical effects, an entity which on the scale of perfection of spiritual beings occupies the very lowest degree. This spirit of nature is12

Among these phenomena unexplainable by purely mechanical forces, of which Henry More knows, alas, a great number, including sympathetic cures and consonance of strings (More, needless to say, is a rather bad physicist), the most important is gravity. Following Descartes, he no longer considers it an essential property of body, or even, as Galileo still did, an unexplainable but real tendency of matter; but—and he is right—he accepts neither the Cartesian nor the Hobbesian explanation of it. Gravity cannot be explained by pure mechanics and therefore, if there were in the world no other, non-mechanical, forces, unattached bodies on our moving earth would not remain on its surface, but fly away and lose themselves in space. That they do not is a proof of the existence in nature of a "more than mechanical," "spiritual" agency.

More writes accordingly in the preface to The Immortality of the Soul,13

As a matter of fact the Antidote against Atheism had already pointed out that stones and bullets projected upwards return to earth—which, according to the laws of motion, they should not do; for,14

Indeed, without the action of a non-mechanical principle all matter in the universe would divide and disperse; there would not even be bodies, because there would be nothing to hold together the ultimate particles composing them. And, of course, there would be no trace of that purposeful organization which manifests itself not only in plants, animals and so on, but even in the very arrangement of our solar system. All that is the work of the spirit of nature, which acts as an instrument, itself unconscious, of the divine will.

So much for the spirit of nature that pervades the whole universe and extends itself in its infinite space. But what about this space itself? the space that we cannot conceive if not infinite—that is, necessary—and that we cannot "disimagine" (which is a confirmation of its necessity) from our thought? Being immaterial it is certainly to be considered as spirit. Yet it is a "spirit" of quite a special and unique kind, and More is not quite sure about its exact nature. Though, obviously, he inclines towards a very definite solution, namely towards the identification of space with the divine extension itself, he is somewhat diffident about it. Thus he writes:15

for which the Cartesians require the presence of matter, asserting that material extension alone can be measured, an assertion which leads inevitably to the affirmation of the infinity and the necessary existence of matter. But we do not need matter in order to have measures, and More can pursue:16

There is also another way of answering this Objection, which is this; that this Imagination of Space is not the imagination of any real thing, but only of the large and immense capacity of the potentiality of the Matter, which we can not free our Minds from but must necessarily acknowledge that there is indeed such a possibility of Matter to be measured upward, downward, everyway in infinitum, whether this corporeal Matter were actually there or no; and that though this potentiality of Matter and Space be measurable by furloughs, miles, or the like, that it implies no more real Essence or Being, than when a man recounts so many orders or Kindes of the Possibilities of things, the compute or number of them will infer the reality of their Existence.

But if the Cartesians would urge us further and insist upon the impossibility of measuring the nothingness of void space,17

And if they urge still further and contend, that . . . distance must be some real thing . . . I answer briefly that Distance is nothing else but the privation of tactual union and the greater distance the greater privation . . .; and that this privation of tactual union is measured by parts, as other privations of qualities by degrees; and that parts

But if this will not satisfie, ’tis no detriment to our cause. For if after the removal of corporeal Matter out of the world, there will be still Space and distance, in which this very matter, while it was there, was also conceived to lye, and this distant Space cannot but be something, and yet not corporeal, because neither impenetrable nor tangible, it must of necessity be a substance Incorporeal, necessarily and eternally existent of it self: which the clearer Idea of a Being absolutely perfect will more fully and punctually inform us to be the Self-subsisting God.

We have seen that, in 1655 and also in 1662, Henry More was hesitating between various solutions of the problem of space. Ten years later his decision is made, and the Enchiridium metaphysicum (1672) not only asserts the real existence of infinite void space against all possible opponents, as a real precondition of all possible existence, but even presents it as the best and most evident example of non-material—and therefore spiritual—reality and thus as the first and foremost, though of course not unique, subject-matter of metaphysics.

Thus Henry More tells us that "the first method for proving the uncorporeal things" must be based on18

Henry More seems to have completely forgotten his own uncertainty concerning the question; in any case he does not mention it and pursues:19

Descartes remains, as we see, the chief adversary of Henry More; indeed, as More discovered meanwhile, by his denial both of void space and of spiritual extension, Descartes practically excludes spirits, souls, and even God, from his world; he simply leaves no place for them in it. To the question "where?," the fundamental question which can be raised concerning any and every real being—souls, spirits, God—and to which Henry More believes he can give definite answers (here, elsewhere or—for God—everywhere), Descartes is obliged, by his principles, to answer: nowhere, nullibi. Thus, in spite of his having invented or perfected the magnificent a priori proof of the existence of God, which Henry More embraced enthusiastically and was to maintain all his life, Descartes, by his teaching, leads to materialism and, by his exclusion of God from the world, to atheism. From now on, Descartes and the Cartesians are to be relentlessly criticized and to bear the derisive nickname of nullibists.

Still, there are not only Cartesians to be combatted.

[paragraph continues] There is also the last cohort of Aristotelians who believe in a finite world, and deny the existence of space outside it. They, too, have to be dealt with. On their behalf Henry More revives some of the old mediaeval arguments used to demonstrate that Aristotelian cosmology was incompatible with God's omnipotence.

It cannot be doubted, of course, that if the world were finite and limited by a spherical surface with no space outside it,20

Thirdly, that it would be absolutely impossible for God to create another world; or even two small bronze spheres at the same time, in the place of these two worlds, as the poles of the parallel axes would coincide because of the lack of an intermediate space.

Nay, even if God could create a world out of these small spheres, closely packed together (disregarding the difficulty of the space that would be left void between them), He would be unable to set them in motion. These are conclusions which Henry More, quite rightly, believed to be indigestible even for a camel's stomach.

Yet Henry More's insistence on the existence of space "outside" the world is, obviously, directed not only against the Aristotelians, but also against the Cartesians to whom he wants to demonstrate the possibility of the limitation of the material world, and at the same time, the mensurability, that is, the existence of dimensions (that now are by no means considered as merely "notional"

determinations) in the void space. It seems that More, who in his youth had been such an inspired and enthusiastic adherent of the doctrine of the infinity of the world (and of worlds), became more and more adverse to it, and would have liked to turn back to the "Stoic" conception of a finite world in the midst of an infinite space, or, at least, to join the semi-Cartesians and reject Descartes’ infinitization of the material world. He even goes so far as to quote, with approval, the Cartesian distinction of the indefiniteness of the world and the infinity of God; interpreting it, of course, as meaning the real finiteness of the world opposed to the infinity of space. This, obviously, because he understands now much better than twenty years previously the positive reason of the Cartesian distinction: infinity implies necessity, an infinite world would be a necessary one. . . .

But we must not anticipate. Let us turn to another sect of philosophers who are at the same time More's enemies and allies.21

It is, moreover, worth while mentioning that those philosophers who made the world finite (such as Plato, Aristotle

As the admission of an infinite space seems thus to be, with very few exceptions, a common opinion of mankind, it may appear unnecessary to insist upon it and to make it an object of discussion and demonstration. More explains therefore that22

overcome, I shall present and reveal all the subterfuges by which the Cartesians want to elude the strength of my demonstrations, and I shall reply to them.

I must confess that Henry More's answers to the "principal means that the Cartesians used in order to evade the strength of the preceding demonstrations" are sometimes of very dubious value. And that "the refutation of them all" is, as often as not, no better than some of his arguments.

Henry More, as we know, was a bad physicist, and he did not always understand the precise meaning of the concepts used by Descartes—for instance, that of the relativity of motion. And yet his criticism is extremely interesting and, in the last analysis, just.23

[paragraph continues] From this definition, objects Henry More, it would follow that a small body firmly wedged somewhere between the axis and the circumference of a large rotating cylinder would be at rest, which is obviously false. Moreover, in this case, this small body, though remaining at rest, would be able to come nearer to, or recede from, another body P, placed immobile, outside the rotating cylinder. Which is absurd as " it supposes that there can be an approach of one body to another, quiescent, one without local motion."

Henry More concludes therefore:25

More's error is obvious. It is clear that, if we accept the Cartesian conception of the relativity of motion, we no longer have any right to speak of bodies as being absolutely "in motion" or "at rest" but have always to add the point or frame of reference in respect to which the said body is to be considered as being at rest or in motion. And that, accordingly, there is no contradiction in stating that the selfsame body may be at rest in respect to its surroundings and in motion in respect to a body placed farther away, or vice versa. And yet Henry More is perfectly right: the extension of the relativity of motion to rotation—at least if we do not want to restrict ourselves to pure kinematics and are dealing with real, physical objects—is illegitimate; moreover, the Cartesian definition, with its more than Aristotelian insistence on the vicinity of the points of reference, is wrong and incompatible with the very principle of relativity. It is, by the way, extremely probable that Descartes thought it out not for purely scientific reasons, but in order to escape the necessity of asserting the motion of the earth and to be able to affirm—with his tongue in his cheek—that the earth was at rest in its vortex.

It is nearly the same concerning More's second argument against the Cartesian conception of relativity, or, as More calls it, "reciprocity" of motion. He claims26

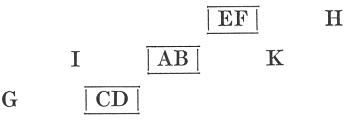

Thus for instance, let us take three bodies, CD, EF and AB, and let EF move towards H, whilst CD moves

towards G, and AB remains fixed to the earth. Thus it does not move and yet moves at the same time: who can say anything more absurd? And is it not evident27

Henry More, it is clear, cannot transform the concept of motion into that of a pure relation. He feels that when bodies move, even if we consider them as moving in respect to each other, something happens, at least to one of them, that is unilateral and not reciprocal: it really moves, that is, changes its place, its internal locus. It is in respect to this "place" that motion has to be conceived and not in respect to any other, and therefore28

In other terms, relative motion implies absolute motion and can only be understood on the basis of absolute motion and thus of absolute space. Indeed, when a cylindrical body is in circular motion, all its internal points not only change their position in respect to its surrounding surface, or a body placed outside it: they move, that is, pass

through some extension, describe a trajectory in this extension which, therefore, does not move. Bodies do not take their places with them, they go from one place to another. The place of a body, its internal locus, is not a part of the body: it is something entirely distinct from it, something that is by no means a mere potentiality of matter: a potentiality cannot be separated from the actual being of a thing, but is an entity, independent of the bodies that are and move in it. And even less is it a mere "phansy,"29 as Dr. Hobbes has tried to assert.

Having thus established, to his own satisfaction, the perfect legitimacy and validity of the concept of space as distinct from matter and refuted their merging together in the Cartesian conception of " extension " Henry More proceeds to the determination of the nature and the ontological status of the corresponding entity.

"Space," or "inner locus," is something extended. Now, extension, as the Cartesians are perfectly right in asserting, cannot be an extension of nothing: distance between two bodies is something real, or, at the very least, a relation which implies a fundamentum reale. The Cartesians, on the other hand, are wrong in believing that void space is nothing. It is something, and even very much so. Once more, it is not a fancy, or a product of imagination, but a perfectly real entity. The ancient atomists were right in asserting its reality and calling it an intelligible nature.

The reality of space can be demonstrated also in a somewhat different manner; it is certain30

It is therefore necessary that, because it is a real attribute, some real subject support this extension. This argumentation is so solid that there is none that could be stronger. For if this one fails, we shall not be able to conclude with any certainty the existence in nature of any real subject whatever. Indeed, in this case, it would be possible for real attributes to be present without there being any real subject or substance to support them.

Henry More is perfectly right. On the basis of traditional ontology—and no one in the seventeenth century (except, perhaps, Gassendi, who claims that space and time are neither substances nor attributes but simply space and time) is so bold or so careless as to reject it or to replace it by a new one—his reasoning is utterly unobjectionable. Attributes imply substances. They do not wander alone, free and unattached, in the world. They cannot exist without support, like the grin of the Cheshire cat, for this would mean that they would be attributes of nothing. Even those who, like Descartes, modify traditional ontology by asserting that the attributes reveal to us the very nature, or essence, of their substance—Henry More sticks to the old view that they do not—maintain the fundamental relationship: no real attribute without real substance. Henry More, therefore, is perfectly right,

too, in pointing out that his argumentation is built on exactly the same pattern as the Cartesian and31

Moreover, Henry More's conclusion from extension to the underlying and supporting substance is exactly parallel to that of Descartes31

To sum up: Descartes was right in looking for substance to support extension. He was wrong in finding it in matter. The infinite, extended entity that embraces and pervades everything is indeed a substance. But it is not matter. It is Spirit; not a spirit, but the Spirit, that is, God.

Space, indeed, is not only real, it is something divine. And in order to convince ourselves of its divine character we have only to consider its attributes. Henry More proceeds therefore to the32

When we shall have enumerated those names and titles appropriate to it, this infinite, immobile, extended [entity] will appear to be not only something real (as we have just pointed out) but even something Divine (which so certainly is found in nature); this will give us further assurance that it cannot be nothing since that to which so many and such magnificent attributes pertain cannot be nothing. Of this kind are the following, which metaphysicians attribute particularly to the First Being, such as: One, Simple, Immobile, Eternal, Complete, Independent, Existing in itself, Subsisting by itself, Incorruptible, Necessary, Immense, Un-created, Uncircumscribed, Incomprehensible, Omnipresent, Incorporeal, All-penetrating, All-embracing, Being by its essence, Actual Being, Pure Act.

There are not less than twenty titles by which the Divine Numen is wont to be designated, and which perfectly fit this infinite internal place (locus) the existence of which in nature we have demonstrated; omitting moreover that the very Divine Numen is called, by the Cabalists, MAKOM, that is, Place (locus). Indeed it would be astonishing and a kind of prodigy if the thing about which so much can be said proved to be a mere nothing.

Indeed, it would be extremely astonishing if an entity eternal, untreated, and existing in and by itself should finally resolve into pure nothing. This impression will only be strengthened by the analysis of the "titles" enumerated by More, who proceeds to examine them one by one:33

But from the Simplicity its Immobility is easily deduced. For no Infinite Extended [entity] which is not co-augmented from parts, or in any way condensed or compressed, can be moved, either part by part, or the whole [of it] at the same time, as it is infinite, nor [can it be] contracted into a lesser space, as it is never condensed, nor can it abandon its place, since this Infinite is the innermost place of all things, inside or outside which there is nothing. And from the very fact that something is conceived as being moved, it is at once understood that it cannot be any part of this Infinite Extended [entity] of which we are speaking. It is therefore necessary that it be immovable. Which attribute of the First Being Aristotle celebrates as the highest.

Absolute space is infinite, immovable, homogeneous, indivisible and unique. These are very important properties which Spinoza and Malebranche discovered almost at the same time as More, and which enabled them to put extension—an intelligible extension, different from that

which is given to our imagination and senses—into their respective Gods; properties that Kant—who, however, with Descartes, missed the indivisibility—was to rediscover a hundred years later, and who, accordingly, was unable to connect space with God and had to put it into ourselves.

But we must not wander away from our subject. Let us come back to More, and More's space34

We see it at once: space is eternal and therefore uncreated. But the things that are in space by no means participate in these properties. Quite the contrary: they are temporal and mutable and are created by God in the eternal space and at a certain moment of the eternal time. Space is not only eternal, simple and one. It is also35

It is indeed not only Eternal but also Independent, not only of our Imagination, as we have demonstrated, but of anything whatever, and it is not connected with any other thing or. supported by any, but receives and supports all [things] as their site and place.

It must be conceived as Existing by itself because it is totally independent of any other. But of the fact that it

Indeed, we cannot "disimagine" space or think it away. We can imagine, or think of, the disappearance of any object from space; we cannot imagine, or think of, the disappearance of space itself. It is the necessary presupposition of our thinking about the existence or non-existence of any thing whatever.36

Herefrom we perceive that it is incomprehensible. How indeed could a finite mind comprehend that which is not comprehended by any limit?

Henry More could have told us, here too, that he was using, though of course for a different end, the famous arguments by which Descartes endeavoured to prove the indefinity of material extension. Yet he may have felt that not only the goal of the argument, but also its very meaning, opposed it to that of Descartes. Indeed, the progressus in infinitum was used by Henry More not for denying, but for asserting the absolute infinity of the extended substance, which37

It is even not undeservedly called Being by essence in contradistinction to being by participation, because Being by itself and being Independent it does not obtain its essence from any other thing.

Furthermore, it is aptly called being in act as it cannot but be conceived as existing outside of its causes.

The list of "attributes" common to God and to space, enumerated by Henry More, is rather impressive; and we cannot but agree that they fit fairly well. After all, this is not surprising: all of them are the formal ontological attributes of the absolute. Yet we have to recognize Henry More's intellectual energy that enabled him not to draw back before the conclusions of his premises; and the courage with which he announced to the world the spatiality of God and the divinity of space.

As for this conclusion, he could not avoid it. Infinity implies necessity. Infinite space is absolute space; even more, it is an Absolute. But there cannot be two (or many) absolute and necessary beings. Thus, as Henry More could not accept the Cartesian solution of the indefiniteness of extension and had to make it infinite, he was eo ipso placed before a dilemma: either to make the material world infinite and thus a se and per se, neither needing, nor even admitting, God's creative action; that is, finally, not needing or even not admitting God's existence at all.

Or he could—and that was exactly what he actually did—separate matter and space, raise the latter to the dignity of an attribute of God, and of an organ in which

and through which God creates and maintains His world, a finite world, limited in space as well as in time, as an infinite creature is an utterly contradictory concept. That is something that Henry More acknowledges not to have recognized in his youth when, seized by some poetic furor, he sang in his Democritus Platonissans a hymn to the infinity of the worlds.

To prove the limitation in time is not very difficult: it is sufficient, according to More, to consider that nothing can belong to the past if it did not become "past" after having been "present"; and that nothing can ever be "present" if it did not, before that, belong to the future. It follows therefrom that all past events have, at some time, belonged to the future, that is, that there was a time when all of them were not yet "present," not yet existent, a time when everything was still in the future and when nothing was real.

It is much more difficult to prove the limitation of the spatial extension of the (material) world. Most of the arguments alleged in favor of the finiteness are rather weak. Yet it can be demonstrated that the material world must, or at least can, be terminated, and therefore is not really infinite.

The circle is closed. The conception that Henry More ascribed to Descartes—though falsely—and so bitterly criticized in his youth, has demonstrated its good points. An indeterminately vast but finite world merged in an infinite space is the only conception, Henry More sees it now, that enables us to maintain the distinction between the contingent created world and the eternal and a se and per se existing God.

By a strange irony of history, the κενόν of the godless atomists became for Henry More God's own extension, the very condition of His action in the world.